After the trilogy of posts about understanding what happens to meat when you cook it in terms of juiciness, tenderness, succulence, flavor, and appearance, another important subject to cover is food safety. This post does not just apply to meat, but also to other animal-based foods such as seafood, and plant-based foods such as vegetables. Unfortunately, a lot of rules and guidelines about food safety are too simplistic or even wrong. In the latter case that usually means erring on the side of caution, which means that the food may be safe, but also unpalatable. I have also noticed that many people make inconsistent choices when it comes to food safety, accepting high risks while at the same time refusing to take smaller risks.

This pork tenderloin has been cooked to a core temperature of 57C/135F for an hour, and is still very much pink inside. According to many rules and guidelines, this would be considered unsafe, because they say pork should be cooked well done and/or to a core temperature of at least 71C/160F. Would you eat the pork in the photo if I served it to you?

Is the pink pork more or less safe compared to sushi? Do you eat sushi?

Is the pink pork more or less safe than a steak, served rare? Do you eat (medium) rare steak?

Is the pink pork more or less safe than a salad? Do you eat salads?

Is pink pork more or less safe than carpaccio? Do you eat carpaccio?

Read on to understand more about food safety, so you can make consistent choices in what you do and do not consider safe enough to eat.

First of all, eating food always has some risk involved. Even if it it was boiled and thus sterilized, there may be a toxin inside that survives such temperatures, or it may be contaminated after it was boiled. The only way to eliminate all risk of getting sick from food is not eating at all. In other words, you have to accept some risk when you eat food. This also means that even if you follow the guidelines in this article (or the official rules for that matter), you may still get sick. And that I can’t accept responsibility for any foodborne illness that results of following the guidelines in this article. Also, if you work in a restaurant, you have to follow the official rules. Otherwise you risk fines or being closed down. This article does not substitute regulations.

Back to the comparison of pink pork, rare steak, sushi, salad, and carpaccio. From a statistical point of view, the pink pork actually has the lowest chance of making you sick. Because it has been cooked to 57C/135F for an hour, the pork has been pasteurized throughout. If the core of the meat has reached 57C/135F and then held at this temperature for at least 40 minutes, at least 99.99997% of any pathogens present in the pork have been killed. The reason for cooking pork well done or to a core temperature of 71C/160F was due to contamination with trichinella. However, trichinella can even be killed by heating the pork only to 49C/120F, if held at that temperature for long enough (21 hours). (At 71C/160F it will be killed in a few seconds.)

I will explain more about the combination of time and temperature below.

But first, let’s look at the risk of the other foods in the photos. The sushi and carpaccio are no-brainers, as they are served raw. I am not saying they are unsafe, but the risk they carry is higher than that of the pink pork.

The salad actually falls in the same category! A common misconception is that animal-based foods are more likely to be contaminated than plant-based foods. Statistically speaking, that is simply not true. Large-scale washing of salad leaves and the like in processing facilities can make it worse, because it can spread the contamination by way of the water used for the washing. If you look again at the photo of the pork, the sage may actually be more dangerous than the pork.

Most contamination of meat is on the surface. Any pathogens present on the outside of the steak will be killed by searing it. However if the steak was tenderized mechanically by inserting needles or small blades into it, a contamination on the surface may have been pushed into the interior. In that case, searing the outside will not help and only pasteurization as done with the pork will make it safe. And so unlike popular belief, properly cooked pink pork can actually be safer to eat than steak.

The effect of time and temperature on bacteria

The following facts about bacteria are relevant to food safety:

- You can get sick from eating bacteria themselves (if you eat enough of them) or a toxin they produce. The latter is called food poisoning, because bacteria have poisoned the food. The most notorious example of this is botulism.

- Freezing does not kill bacteria. They grow very slowly at temperatures below 5C/40F, which is why refrigerators work so well to preserve food.

- When the temperature increases, bacteria will start to grow more quickly. Salmonella grows at the highest rate at 41.5C/107F.

- If the temperature increases even more, the growth will drop off quickly and above a certain temperature they will start to die. Salmonella starts to die at 49C/120F.

- The higher the temperature, the more quickly bacteria will die. To kill 99.99997% of salmonella it takes 21 hours at 49C/120F, but only 1 minute at 61C/142F. This is why guidelines for cooking food to make it safe to eat should always include both a temperature and a time.

- When bacteria are killed by heat, they may leave spores behind. You can think of the spores as “eggs” from which new bacteria can grow if the conditions turn favorable again (i.e. temperatures higher than 5C/40F or lower than 52C/126F). This is why after cooking, you should either keep the food warm at at least 54C/129F or chill it quickly to refrigerator temperatures.

The table above shows at what temperatures and acidity bacteria can reproduce.

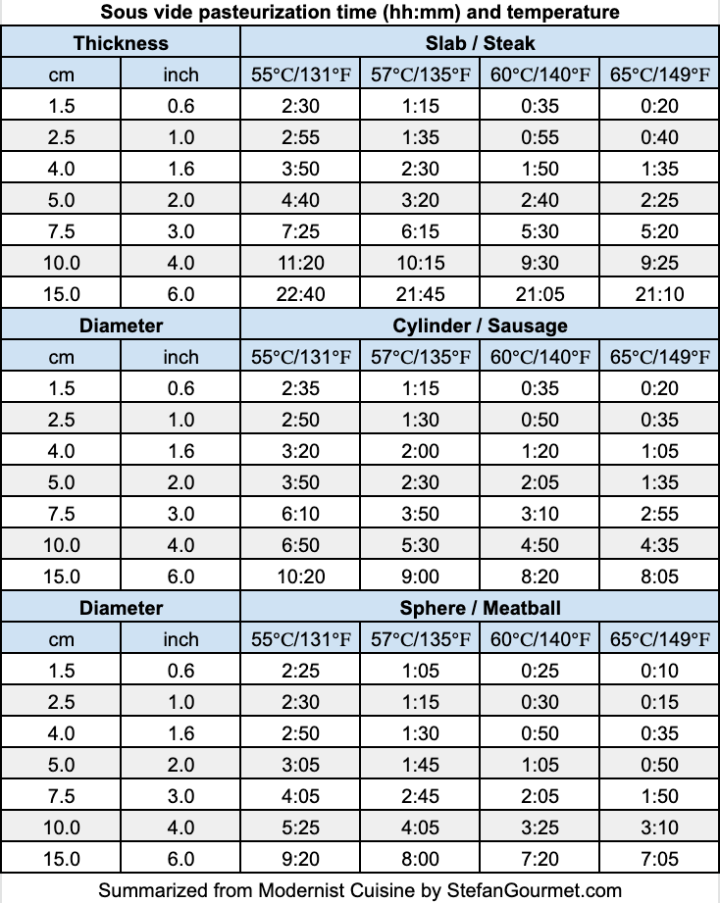

Salmonella is more resistant to heat than other pathogens that are most relevant for food safety and it poses a serious threat in its own right, which is why the following table of time and temperature to get a 99.99997% reduction of salmonella can be considered a good guideline for food safety in general (source: Modernist Cuisine). The usual term for food that has been heated according to this is standard is “pasteurized”, named after the inventor Louis Pasteur (who also discovered that germs could cause sickness in the first place).

Pasteurization times

The following combinations of cooking time and temperature will reduce salmonella by 99.99997%. The time needed to bring the core to this temperature should be added, and then the food should be held at the indicated temperature for the indicate time to achieve pasteurization. The times are indicated in hours (h), minutes (m), and seconds (s). Please note that a reduction of 99.99997% is sufficient in real-life situations in which the food has been treated sensibly. If salmonella has first been allowed to grow by a lot (i.e. by holding the food for a long time at a temperature around 41.5C/107F), such a reduction may not be enough.

Please note that an accurate thermometer is important when cooking at a low temperature. If you aren’t sure about your thermometer, it is best to assume it is off by a couple of degrees and adjust the cooking time accordingly to achieve true pasteurization.

How to reduce the risk of foodborne illness

As I’ve pointed out above, you can’t eliminate all risk of foodborne illness. It is however possible to reduce the risk to acceptable levels without cooking everything to death. This is especially true as long as you are not cooking for susceptible people, including infants, elderly, and people with a compromised immune system.

The most important factor is hygiene. Keep your kitchen clean and wash your hands. Cross-contamination is the biggest source of foodborne illness. I assume that everybody is aware of this, so I’m going to concentrate on what cooking practices will allow you to cook and serve tasty food with a reasonable level of risk.

Intact muscle meat: cook the outside

Intact muscle meat from commercially farmed beef, pork, lamb, venison, duck, ostrich, or emu can be assumed to be sterile on the inside, so any contamination will be on the outside. Simply searing the meat is therefore sufficient. (In theory, it would be enough to bring the outside only to 77C/170F for one second, but searing will go far beyond that.) Intact means that the meat has not be handled in such a way (such as tenderizing by inserting small blades or needles, or injecting marinades, or grinding) that a contamination from the outside could get inside the meat.

If you serve the meat raw (e.g. carpaccio) the risk is higher, but can be reduced by careful washing. Searing the outside may still be a good idea.

All other types of meat: pasteurize

This applies to:

- poultry and eggs

- wild game meat

- meat that has been handled in such a way that a contamination from the outside could have gotten inside, such as grinding, mechanical tenderizing, or injecting

In all of these cases, make it safe to eat by pasteurizing according to the table below.

Fish

The problem with fish is that pasteurizing it will overcook it. As most fish is intact muscle meat, the problem is not with a bacterial contamination on the outside. The problem is with parasites. Saltwater fish that live close to the shore may harbor such parasites, which can be killed by pasteurizing (thus overcooking the fish) or by freezing. If the fish has not been frozen, it is up to you whether you want to run the risk. Freshwater fish, farmed salmon, or fish that live far from the coast like tuna and swordfish are fine to eat raw or cooked to any time and temperature you like.

Crustaceans

Lobster, crab, and shrimp: if you started with a live crustacean, then you can eat it raw. Otherwise, blanch the outside or pasteurize. Traditional steaming or boiling will definitely do the trick.

Shellfish

There is some risk with eating oysters or clams raw, as they filter lots of seawater and thus can be contaminated. Pasteurize to eliminate this risk. Traditional steaming will definitely do the trick.

Fruit and vegetables

Just as with meat, the contamination is usually on the outside. If you are not going to cook the vegetable, then wash or peel carefully and watch out for cross-contamination. If you are going to cook, then washing is not as important as the heat will kill any pathogens.

Further reading

This post has been based upon Volume 1, chapters 2 and 3 of Modernist Cuisine by Nathan Myhrvold et al.

Quite good information Stefan!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very informative post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderful and wonderfully helpful post, Stefan! In a long lifetime of travelling, much of it in Asia, I have been ill twice: once in Belgium with ‘green baby eels’ in one of the best restaurants in Europe and once, being stupid, eating ceviche sitting for hours on a lunch buffet on a hot day in Papeete. Yes, I do watch water, raw salad ingredients and raw fruit . . . yes, tho’ I adore street food, I’ll have a look how many locals buy! But SO enjoy!! Beef blue>rare wherever, lamb med rare, pork a tad pink, chicken well done! One matter people do not think about: how do all the people in ‘dirty’ countries not get ill and die in droves: one’s body DOES build up immunity to many of the bugs: actually a few glasses of wine are known to ‘sterilize’ one’s innards post an ‘iffy’ meal . . . the next time around your GIT will say: ‘oh buddy, I can manage that’ 🙂 !!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great post! I will say that we Wards live in the wild side (pun intended). 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot. I’m going to save this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well written and informative post, Stefan. I wish all bloggers would read it. You wold not believe some of the things I’ve read. One even stated that it was OK to serve “pink chicken”. That’s one dinner party I’ll be sure to avoid.

LikeLiked by 1 person