Italy has officially made history as the first nation to have its entire culinary system protected as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. In this post, I’ll explore the significance of this designation and weigh the official submission against my 25 years of experience with Italian cooking and culture. I also address the recent Guardian article claiming that traditional Italian cuisine is merely a “myth”—a provocative take that feels more like a book promotion than a valid historical argument.

The Context: What is UNESCO Intangible Heritage?

UNESCO is best known for its World Heritage List, which includes sites like the Taj Mahal (India), the Pyramids of Giza (Egypt), and Machu Picchu (Peru). Besides this tangible world heritage, from 2003 UNESCO has expanded to safeguard also intangible cultural heritage, maintaining a “Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity”. To get a tradition added to this list, a country must prove the custom is a living part of their culture that fosters global diversity and creativity. The nomination requires a clear plan for its protection, evidence of full consent and participation from the local community, and confirmation that it is already officially recorded in the home country’s national inventory.

The Italians have submitted this file to get “Italian cooking, between sustainability and biocultural diversity” on the list. This submission portrays Italian home cooking as a vital social glue that connects generations through the art of food. It emphasizes “anti-waste” traditions and artisanal techniques that are passed down from grandparents to grandchildren, ensuring that flavors and history aren’t lost to time. It goes on to point out that in Italy, this practice serves as a “language of care,” where preparing a meal is an act of love that fosters community belonging, social inclusion, and physical well-being. Whether in a family kitchen or a public festival, the act of sharing a table becomes a classroom for life, preserving not just culinary skills, but also the gestures, stories, and cultural roots of the Italian people.

The Proof: Testing the UNESCO Criteria

The twentieth session of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, held in New Delhi in December 2025, officially approved Italy’s submission. While this confirms that all formal requirements were met—and no doubt involved a fair amount of international diplomacy—I prefer to look past the paperwork. I am less interested in Italy’s ability to navigate the politics and bureaucracy of UNESCO and more interested in the substance: Is Italian cooking truly the heartbeat of the culture, or is that just a romanticized image on a nomination form?

After experiencing and studying Italian cuisine and culture for over 25 years—learning the language, visiting all of Italy’s regions, and tasting my way through every level of the culinary scene, from humble neighborhood trattorie to Michelin-starred icons; preparing recipes from all over the country, following Italian food blogs, and being invited into Italian homes for authentic home-cooked meals; befriending Italians and engaging in discussions with them about food and cooking; and deepening my understanding of Italian history and culture through reading their novels and watching their movies and TV shows—my answer is a resounding yes.

Let’s examine the UNESCO criteria regarding substance required for the submission file and compare them with my personal experience:

- Authenticity (R.1): A Genuine Living Tradition. Food is very important to Italians. If there is a celebration or even just a gathering of family or friends, food is an important element; it is more than just sustenance. The family lunch on Sunday is an institution. In many Italian novels I’ve read, food and meals are a very important element of setting the scene, often including detailed descriptions of dishes or recipes. A living tradition also means that it should have historic roots and evolve over time. Both are true for Italian cooking. The historic roots are clearly visible in the regional dishes, because you can tell they were created with what was available locally, before the times of refrigeration and fast long-distance transportation. Even today, you only have to go about 10 kilometers inland to see the local dishes changing completely from seafood to meat. And local ingredients feature prominently; for instance, it is easy to recognize recipes from Liguria as many of them contain pine nuts (easily available) and no or a reduced amount of flour (because there was not much space for growing grain). The traditional aspect is also clear in that many recipes popular today can be traced back to historical sources like the book Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well by Pellegrino Artusi (1891). On the other hand, the living aspect is clear in that recipes have evolved and many now famous recipes have emerged only after WW2 (like Carbonara, Tiramisù, and Ciabatta) or have been influenced by Italians in diaspora (like pizza). The recent update of the official recipe for Ragù alla Bolognese is also proof that evolving culinary practices are incorporated into the tradition.

- Global Value (R.2): Visibility, Dialogue, and Sustainability. UNESCO is looking for proof that this heritage helps the entire world communicate and understand each other better. I’ve found it is very easy to strike up a conversation with an Italian about food. They like to discuss and even debate ingredients, recipes, or cooking techniques. The fact that Italians are willing to spend their time debating a recipe with people from outside their borders proves that their heritage encourages intercultural dialogue. Just the mere fact that I, as a Dutchman, am writing this blog now is proof that adding Italian cooking to UNESCO’s list contributes to awareness and dialogue. Sustainability is a clear theme in Italian cooking, as it uses locally sourced ingredients and prevents waste by turning leftovers into new dishes. In Puglia, they even make use of burnt flour that is left in ovens after baking (grano arso).

- Protection (R.3): Safeguarding for Future Generations. I’ve experienced three types of safeguarding measures. The first one is included in Italy’s submission and the most famous: the tradition of passing down recipes and techniques between generations, from the nonnas to their children and grandchildren. There are two others that I consider to be important and are not in the submission, although they actually support the submission’s spirit. The first is that I’ve found that Italians care deeply about their culinary traditions and ‘police’ them fervently. If you don’t know what I mean, try cutting spaghetti or putting cheese on pasta with vongole in front of an Italian, and you’ll find out. This ‘culinary policing’ isn’t just about being strict; it’s a community-led safeguarding effort that ensures the identity of the dish remains intact despite external pressure to simplify or change it. The second is the organized activities to preserve and promote regional products and recipes, like a committee to define the official recipe for Ragù alla Bolognese and depositing that with the chamber of commerce, or publications by the Slow Food movement, including a guidebook Osterie d’Italia with simple restaurants that serve authentic local dishes and books with recipes from those restaurants.

- Community Support (R.4) and Official Recognition (R.5). While these criteria deal with the submission process rather than the actual practice, my experience of how easy it is to befriend Italians through talking about food gives me little doubt about the support of Italians for this submission.

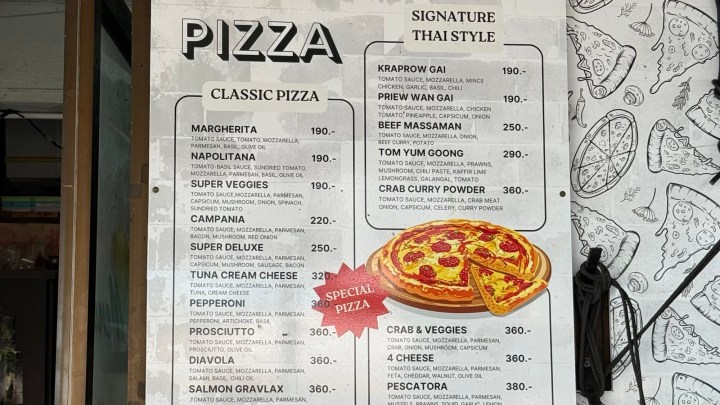

The Contrast: Italy vs. Thailand

The Italian resilience in protecting their culinary traditions becomes even more impressive when compared to my experiences in Thailand, where it was nearly impossible to find authentic local dishes in touristy areas because the food scene has adapted to the tastes and expectations of international visitors. This is striking when you realize that Italy receives more tourists (65-70 million) per year than the size of the local population (59 million), whereas Thailand receives less than 40 million tourists on a population of over 70 million.

My opinion about Grandi’s article in The Guardian

Shortly after UNESCO’s recognition hit the news, I noticed an opinion article in The Guardian by Alberto Grandi entitled “The myth of traditional Italian cuisine has seduced the world. The truth is very different”. He is the author of the book La Cucina Italiana Non Esiste (Italian Cuisine Does Not Exist) and a professor of food history at the University of Parma. In this article, he claims that what Italy submitted was not its actual history but a postcard: beautifully composed, carefully lit, and designed to please, instead of the real, restless, inventive and gloriously impure story of Italian cuisine. Or in other words, he claims that UNESCO has recognized a myth.

However, what was actually submitted and recognized was precisely the living cuisine that evolves in real homes as described by Grandi. Grandi seems to assume that UNESCO would only recognize an ancient, historically pure, culinary canon, whereas in reality it is quite the opposite: UNESCO’s definition of intangible heritage explicitly requires it to be constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment. He makes some valid points in his article, but his claim that UNESCO has inscribed a myth does not follow from the evidence he presents. I believe he has either not read the submission or is spinning a narrative to generate publicity his book. Let’s look more closely at his arguments, one by one:

- Prior Recognitions: His first point is that France and Japan have ‘beaten’ Italy because their cuisines were recognized in 2010 and 2013. This misconstrues the nature of prior recognitions. France’s 2010 inscription honored the gastronomic meal of the French (a ritualized format), and Japan’s 2013 inscription honored washoku (a dietary culture). Italy’s 2025 listing is categorically different: it recognizes the entire national cuisine as living heritage. It is true that Italians were annoyed that culinary traditions of France and Japan were recognized first, but Italy was not late to the same achievement.

- The “Ancient” Argument: Grandi states that “the strength of Italian cuisine has never rested on an ancient, coherent culinary canon”, and that the submission “embalmed a living cuisine”. This is however not what was submitted. He goes on to say that “most of what passes for ancient ‘regional tradition’ was assembled in the late 20th century”. It is true that many popular Italian dishes today evolved in 1945–1965, but you can hardly call that the “late” 20th century. In addition to that, the persistence of these recipes for 60–80 years—across families, towns, and regions—actually demonstrates that these have become a tradition by any reasonable cultural measure. And those recipes have roots that go back a lot longer, for instance to Artusi (1891), but also to the diverse geography of Italy that shaped the differences between regional cuisines.

- Hunger and Survival: Grandi is right that Italian cuisine was shaped by hunger, improvisation, and survival. The famous cucina povera emerged from scarcity and was transmitted across generations. But not mentioning the starvation explicitly in the UNESCO submission is not the same as presenting Italian cooking with sunlit tables and recipes carved in marble, like Grandi suggests. Furthermore, being shaped by scarcity and survival is akin to the history and origin of all cuisines in the world, so not unique to Italian culinary tradition. Although it is true that the Italian cuisine that conquered the world was in part re-invented outside of Italy by Italian emigrants and imported back to Italy (with pizza as the most famous example), that certainly doesn’t mean that the entire Italian culinary tradition was “invented abroad”.

- Adaptability vs. Sovereignty: Grandi states that “culinary sovereigntists” insist on freezing everything in place, while cuisines that change are the ones that survive. I agree that Italian guardianship of culinary traditions can sometimes take things too far, insisting that for an authentic dish very precise local ingredients are required. This is not compatible with the soul of Italian cooking, which is all about using what is available. So yes, the local ingredient would certainly be used if it was available, but if it wasn’t, people would substitute with something that was rather than starve. Grandi has a valid point here, but I fail to see what it has to do with the UNESCO submission. In practice, adaptability is a core component of the safeguarding of culinary traditions like I witnessed them in Italy, and how they are described in Italy’s submission.

- The Postcard Accusation: It is true that a marketing image of Italian cooking exists (and not just invented by the British), but all marketing focuses on the positives and doesn’t show the negatives. And the positives it shows, like families spending hours eating together, have more foundation in reality than Grandi claims. Finally, Grandi speculates about what Italy submitted to UNESCO, rather than evaluating what was actually submitted. He states that only the “real” story of a cuisine “shaped by hunger” would deserve recognition, and suggests that Italy submitted a sentimental narrative (“a postcard”) rather than the rigorous safeguarding framework that UNESCO asks for (and is provided in the dossier that was actually submitted).

My conclusion: the Italian culinary tradition is a living reality, not a marketing myth

The UNESCO recognition of Italian cuisine is not a declaration that Italian food is “better” than any other. Instead, it is a formal acknowledgement of a truth I have witnessed for over a quarter of a century: that in Italy, the kitchen is the soul of the community.

While critics like Alberto Grandi may fret over historical “purity” and the dates of specific recipes, they miss the forest for the trees. A tradition is not defined by its age, but by its vitality. Whether it is a recipe from 1891 or a post-war innovation from 1950, what matters is passing down the tradition, the fierce protection of its identity, and the shared joy of the table.

For the traveler, this UNESCO status is an invitation. It is a reminder to look past the “tourist menus” and seek out those neighborhood trattorie and family tables where the real heritage lives. After 25 years of exploring every corner of this beautiful country, I can tell you that the “postcard” is real—not because it is perfect, but because it is lived every single day.

What do you think? Does Italy’s culinary heritage feel like a “living tradition” to you, or have you found it harder to find the “real thing” in your travels? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

Bravo Stefan! I was just talking to my husband about how Italian restaurants are everywhere, even at hotels in Mexico, including Mexico City. So strange.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Stefan! I am thrilled to be reading your thoughts with which I have agreed for such a long time but lacked the ability and knowledge to express in your terms. Methinks I am rather well-known for my forever ‘spag bol’ harrumphing. Your writing will be kept and passed onto others. Have learned a number of things I did not know myself . . . love your own personal photos from happy days in the country, many of which I remember . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person